by Marc Ornstein

Every forward stroke begins with the all-important catch. It is that moment, beginning when the tip of the blade enters the water and power is 1st applied to it. Correctly done, maximum power will be efficiently applied and minimal correction will be required.

Every forward stroke begins with the all-important catch. It is that moment, beginning when the tip of the blade enters the water and power is 1st applied to it. Correctly done, maximum power will be efficiently applied and minimal correction will be required.

We begin with the wind up: This is where the torso is rotated so that the shoulder of the shaft arm/hand comes forward as far as one can comfortably reach. The grip arm/hand follows, nearly directly above the shaft hand.

Next comes the entry: The blade is driven into the water with a downward motion of the grip arm until the blade is fully or nearly submerged. Care must be taken to assure that the blade is perpendicular to the keel line. The grip is outboard of the gunwale and stacked above the shaft hand, assuring a vertical or nearly vertical paddle shaft. If the grip hand is inboard of the gunwale the blade will be angled outward, creating a sweep component. Likewise, if the grip hand is significantly aft of the shaft hand the blade will be angled such that it will be pressing water downward, wasting energy as it attempts to lift the boat. A clean entry is nearly silent. If there is a splash at the entry, either the grip hand was too far aft of the shaft hand or the entire paddle was being drawn aft (power applied) during the entry phase.

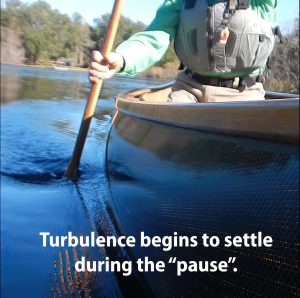

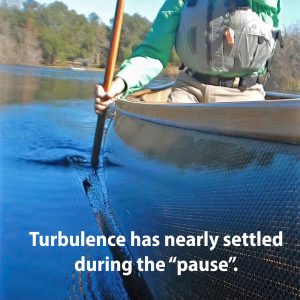

Once the catch has been set, there is a brief, almost imperceptible pause or hesitation while the water “settles” around the blade. This brief pause allows turbulence and air bubbles created by the displacement of water, by the blade, to dissipate. During the pause/hesitation the blade is actually moving, with relation to the hull but at the same rate that the hull is gliding through the water; no faster and no slower. Moving slower would be the equivalent of putting on the brakes. (Note: The pause is not necessary when an in-water recovery is used because the blade has remained submerged.)

|

|

|

The power phase now commences. As the torso unwinds, the paddle is drawn straight back, parallel to the keel line of the canoe. It does not follow the curvature of the hull. If paddling from the stern of a tandem canoe, this is not a problem since the canoe becomes narrower as the paddle travels aft. If paddling solo or in the bow of a tandem the placement must be such that the edge of the blade, closest to the hull is an inch or two away from it so that as it is drawn straight back it does not contact the now, widening hull.

The power phase is exceedingly short. It ends when the blade reaches the paddler’s knee. It is typically less than eighteen inches. It will vary a bit depending upon the size of the paddler and whether they are kneeling or sitting. If paddling hit and switch style, recovery, (for the next stroke) begins at this point. If a J stroke or other correction is to be applied, the paddle path continues, gently, farther aft, not for the application of power but so that an effective correction can be made, nearer the stern.

Not all of us paddle for maximum efficiency and speed, all the time. When paddling in a more relaxed fashion, the wind up may be toned down a bit and the brief pause omitted, but when one wants to secure that coveted campsite on the point, make it home before the weather closes in or just beat your buddies to the takeout, the all-important catch might just make the difference.