By Paul Klonowski

There are many variations of the J Stroke being used these days. This essay will discuss yet another, which I propose adds some efficiency to the effort, reducing strain on the arms and hands.

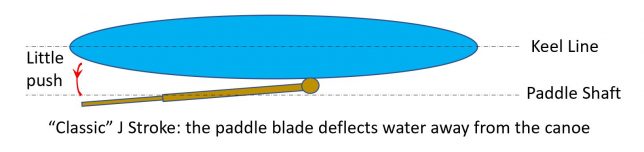

Classically, the J is taught as a power stroke, combined with rolling the blade’s powerface away from the canoe, and giving a little “push” to bring the yaw (sideways deflection of the canoe) back into line, such that the canoe is still heading the direction the paddler wants to go.

The issue with the “little push” is that it adds a slight braking action, countermanding the power stroke that the paddler just applied to the water. Essentially, even a little sideways push is slowing the canoe. How can this braking effect be minimized?

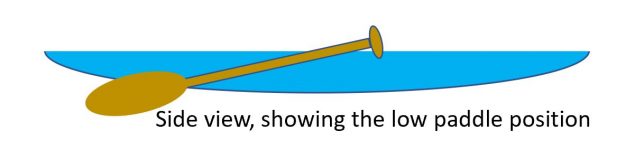

To begin, the paddler may need to turn the shoulders about 45 degrees to the paddle side, either with some good torso rotation, or simply by turning the kneeling position, to “Face Your Work.” This helps to get the grip hand out over the water, and to keep the paddle low.

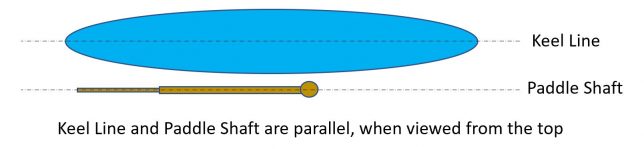

When the Power Phase of the stroke is completed, the blade is turned just like the J Stroke, but at the end of the power phase of the J, the blade must be positioned parallel to the canoe’s keel line, with the lateral axis of the blade in a vertical plane, perpendicular to the water surface. The “Little Push” away from the canoe is skipped:

For many people, getting the blade turned all the way vertical is more comfortable using a palm roll, to ease strain on the wrist, so while the grip hand appears to be in position similar to performing a stern rudder or stern pry, the powerface of the blade has not changed between the power phase of the forward stroke, into the J phase. The paddle in the water has the same smooth action as the classic J, but the hand position on the grip has rotated 180 degrees, and the shaft hand can choke up quite a bit on the shaft. Keep the entire paddle low, much like for initiating a Christie… the grip hand can be as low as you like, and still maintain an erect posture. Just make sure the entire blade is in the water.

While the canoe has forward momentum, and the paddle is held low with the blade vertical in the water, the blade will keep the canoe going straight. Applying a slight angle to the paddle a little away from vertical, one way or the other, will impart a gentle turning momentum to the canoe.

If the top tip of the grip itself is rotated a little bit away from the canoe, the blade also turns with it, and the canoe turns toward the paddle side. If the top tip of the grip is rotated a little bit toward the canoe, the blade again turns with it, and turns the canoe away from the paddle side. Think of it as “The canoe turns in the direction of the paddle rotation.”

When coasting in a level canoe, the paddler should be able to make the canoe turn one way, then the other, with the only effort expended being to rotate the blade from one side to the other. The directional change may take a few seconds, so being patient helps. Once the paddler gets the feel of this, heeling the canoe the appropriate direction will enhance the turns as well, as discussed in A Pitch for Heeling pt1 and Heeling vs Carving.

The keys to this are to keep the paddle’s shaft parallel to the keel line of the canoe, when viewed from the top. The grip hand must be out over the water, such that if the paddler were to drop the paddle, the paddle would not hit the canoe. Next, the blade must start out oriented vertically in the water, also when viewed from the top. Once that is established, use the rotation of the blade to impart the turning action. The last, and perhaps most important, key is to ssslllooowww dddooowwwnnn… you’ve probably heard that before!

Note that when using this technique, turning the canoe toward the paddle side will be a stronger, more immediate turning action than turning away from the paddle side.

The same effect can be executed while paddling in reverse. Perform the Reverse J, keeping the grip hand out over the water, but again skip the “Little Push” away from the canoe; note that in reverse, no palm roll is required, just point the thumb of the grip hand down. Choke up on the paddle shaft as the J is beginning, so the shaft hand moves closer to the grip hand; the shaft hand should be holding the paddle very loosely. The thumb of the grip hand should be pointing down into the elbow, or even into the forearm, of the shaft hand. It sounds complicated in prose, but is really a smooth and natural movement.

The same effect can be executed while paddling in reverse. Perform the Reverse J, keeping the grip hand out over the water, but again skip the “Little Push” away from the canoe; note that in reverse, no palm roll is required, just point the thumb of the grip hand down. Choke up on the paddle shaft as the J is beginning, so the shaft hand moves closer to the grip hand; the shaft hand should be holding the paddle very loosely. The thumb of the grip hand should be pointing down into the elbow, or even into the forearm, of the shaft hand. It sounds complicated in prose, but is really a smooth and natural movement.

At that stage, the paddle should be parallel to the keel line, with the blade vertical in the water, and the canoe will travel backward in a straight line. To turn, again rotate the grip a little bit into the direction of the intended turn, and the canoe will start turning that direction. Reverse the rotation, and be patient, and the canoe will turn the other direction. And again, heeling the canoe appropriately will enhance the turning action.

Note that some folks have an easier time learning the J Stroke if they learn the Reverse J first… for the Reverse J, the paddle is out in front of the paddler, so it’s easy to see what the paddle is doing, and how it affects the canoe’s motion. This is also true for this technique. Don’t hesitate to try this in reverse!

The forward technique is used by the stern paddler in a tandem while moving forward, the reverse technique is used by the bow paddler in a tandem while moving backward, and either technique can be used by a solo paddler. Note that, as the turn gets about as far as the paddler wants it to go, the paddle can be simply sliced back into position for the next stroke, whether it’s forwards or backwards.

The turns initiated using this method are gentle, so if you’re in fast current, wind, or waves, more powerful correction strokes will be more appropriate. Once you get accustomed to using this technique, though, you’ll find it works on more than just flat, calm water. Beyond that, any FreeStyle Maneuver can be initiated with this minimal effort! Just slice from the rotated paddle position into the Placement, and go from there. In a formal FreeStyle Competition, you may lose points for using this technique… the judges want to see the Initiation, which will be largely hidden. But for Exhibition, Functional FreeStyle, or every day paddling applications, that formal Initiation isn’t a concern.

In the final analysis, the question does arise: Is this even a J Stroke any more? The blade isn’t kicked out away from the canoe… should we call it a “Lazy J?”