The J-stroke reconsidered

By Marc Ornstein

When I first began canoeing, more years ago than I care to count, I was told that learning the J stroke was the holy grail to keeping the boat going straight. Over the decades since, I’ve found that notion to be almost universal with most instructional programs including it very early in the learning curve. The much easier to execute stern pry generally being frowned upon as inefficient and a symbol of poor technique. (An exception would be the whitewater community which prefers the stern pry for the added power it provides.)

While I agree that a properly done J is more efficient, the stern pry is far easier to master. For beginners, struggling to get their craft from point A to point B, teaching the stern pry first (along with hit & switch) makes far more sense. Despite this almost universal emphasis on teaching the J stroke as a basic, almost entry level skill, it is the exception rather than the rule to meet intermediate or even advanced level students who do it well.

Let’s begin with the name of the stroke, J. The proper path of the paddle doesn’t come close to resembling the letter J. If it did, each stroke would propel the boat forward during the catch and power phases then bring it nearly to a standstill during the correction (or J) phase. In fact, that is what I and my fellow instructors most often observe. If the paddle follows a J shaped path through the water, the last portion of the J is essentially a back stroke which is what we teach students to do when they need to stop the canoe while, in fact, our goal is to make a gentle course correction and to keep the canoe moving. We’d be better served by dropping the term “J stroke” and barring the adoption of some catchy new name, calling it what it is; a thumb down stern rudder or arguably a gentle thumb down stern pry. For now, I’ll simply refer to it as a thumb down, stern correction.

In an earlier article I described how to perform a proper/efficient forward stroke and that if done properly, very little correction is necessary. Unless one is fighting strong currents, winds or waves, only a small correction should be necessary to compensate for the yaw induced by the catch and power phase of the forward stroke. With that in mind, think gentle. Also, visualize a very mild rudder which softly guides the canoe as opposed to a hard push away or pry which forcefully deflects the stern. Finally, recalling basic high school science, think of the canoe as a lever with the fulcrum being near the center of the boat. If we want to pivot that lever, we need to apply some force either forward of or behind the fulcrum. The further away from the fulcrum that we apply that force, the less force that will be required. In this case, the force will be applied behind the fulcrum, near the stern. The further back (closer to the stern) it is applied the less force that will be necessary.

Now let’s describe the thumb down, stern correction (what we used to call the J).

● You’ve executed a forward stroke, being careful to keep the power phase short and straight with a vertical shaft. As the blade passes your knee, you minimize the power applied to it allowing it to essentially drift toward the stern (as the canoe moves forward). The blade has continued in a straight line. It has not followed the curvature of the hull.

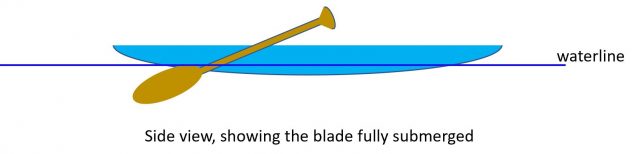

● As the blade is drifting toward the stern you are rotating the grip so that the thumb of your grip hand is pointing downward. By the time your grip hand has reached your hip (or nearly so) the blade is nearly vertical and perpendicular to the surface of the water. Keep the blade fully or near fully submerged. The grip remains low, just a bit above the gunwale.

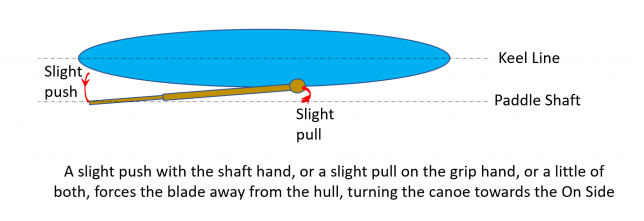

● Now bring the grip a bit inward, toward your hip or push your shaft hand outward slightly or a combination of the two. Either will create a slight angle with the tip of the blade a bit farther away from the boat than the grip end. The blade has now become a rudder, nudging the stern away from it such that the hull will begin to ease back toward the “on” side. Keep the blade well submerged until the desired correction has been accomplished.

If greater correction is necessary, hold onto that rudder a bit longer, bring the grip inward a bit more, or push the blade outward a bit more or some combination of those three things. The important thing is to be gentle. Increasing the angle, more than a little bit, creates a great deal of resistance and wipes away your forward momentum.

Lift the blade vertically, out of the water, turn your thumb (grip hand) back upward (so that it and the blade are horizontal (parallel to the water) and swing the blade forward to begin the next stroke.

Remember these three points:

The entire correction should be done gently.

Keep blade nearly vertical or perpendicular to the water throughout the correction.

Keep the blade fully submerged.

It all sounds easy and it becomes so with practice but turning the thumb down seems unnatural at first and there is an almost universal tendency to begin lifting the blade, from the water, far too soon. Be gentle and patiently give the canoe time to respond. You’ll be rewarded with a smoother, more efficient ride and far less fatigue at the end of the day.

The following two videos illustrate the proper execution of the J Stroke, the 1st in real time and the 2nd at ¼ speed. When watching, take notice that the blade is kept almost fully submerged, throughout the stroke, that it is nearly vertical (perpendicular to the water surface, and that blade angle is only slight, relative to the keel line of the canoe.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iPgPsKPFWYc&feature=youtu.be

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6rCKHzOD8Jw&feature=youtu.be