By Marc Ornstein

Recently, I received an email from a friend and student, requesting assistance. She was having trouble heeling her boat to the rail, even though she was “doing what she saw” in several videos. It got me to thinking about how many times I’ve heard a student say “I’m doing just what you’re doing, but my boat won’t heel like yours”. Often that’s followed by “it must be my boat” or something similar.

In all fairness, there are a very few cases where the canoe is the problem. A very wide and/or flat-bottomed canoe with hard chines may be difficult to heel but such hulls rarely show up at FreeStyle events. I don’t think I’ve ever had a student with such a boat. Invariably, the problem is largely technique. If the student is adamant, arguing that their hull is at fault, I switch boats with them, right then and there, in the middle of the lake. Without fail, their boat, now with me paddling it, heels and behaves as it should, while my previously well-behaved boat instantly adopts the stubborn habits of its new occupant. With no further arguments, we get back to teaching.

Most paddlers think that, in order to heel a canoe, they must lean in the direction of the heel. That (lean) mindset is at the root of the problem. Heeling is accomplished by shifting weight, not by leaning. When you lean in a canoe, you feel (and are) out of balance. The natural tendency is to counter-balance in some manner. If you kneel in a traditional three-point stance (one knee in each chine and butt on the front rail of the seat), then  lean left, you will automatically tend to slide your right foot/knee to the right in order to counter-balance. The result is little or no heel.

lean left, you will automatically tend to slide your right foot/knee to the right in order to counter-balance. The result is little or no heel.

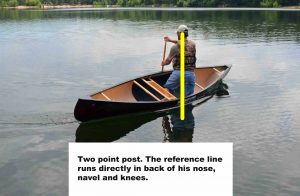

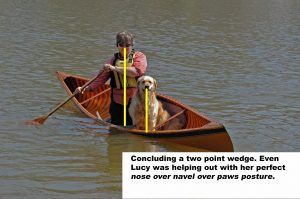

To heel, good posture is the key. Keep your torso vertical and erect. Except for a few esoteric “show” moves, the mantra is nose over navel over knees.

knees.

So, if you want the canoe to heel, you need to shift your weight without leaning. For example, while maintaining a three-point stance, you can heel by pressing down with one knee while easing pressure on the other, all the while keeping your torso vertical. Lifting off the seat a bit and transferring more weight to your knees increases the knee control and adds a bit of pitch. (See “A Pitch for Heeling” https://freestylecanoeing.com/a-pitch-for-heeling-part-1/) With practice, most folks can accomplish significant heel in this manner.

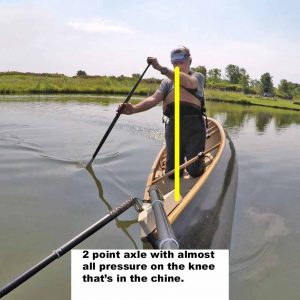

Heeling further requires some repositioning of your body within the canoe. Perhaps the simplest move is to keep one knee in the chine (on the side you want to heel toward), and move the other knee closer to it, again while transferring weight from the seat to your knees. The farther both knees are moved toward or into one chine, the greater the heel. TIP: I often move one knee to the upper part of the chine and brace it there by placing the other knee just below it. With that technique, even most stubborn boats will heel to the rail.

Heeling further requires some repositioning of your body within the canoe. Perhaps the simplest move is to keep one knee in the chine (on the side you want to heel toward), and move the other knee closer to it, again while transferring weight from the seat to your knees. The farther both knees are moved toward or into one chine, the greater the heel. TIP: I often move one knee to the upper part of the chine and brace it there by placing the other knee just below it. With that technique, even most stubborn boats will heel to the rail.

It’s rarely necessary to push things further, but sometimes you just want to have some fun, or show off a bit. Doing so requires you to move around a bit more and involves getting into a transverse or semi-transverse position. Transverse means turning your body to face the onside of the canoe. Semi-transverse is similar except that you only turn partway. Remember, when trying these rotations for the first time, if you lean forward over the gunwale, instead of transferring your weight, you will instinctively drop lower on your knees and stick your “butt out back” (BOB) in order to counter-balance. Again, the result is little or no heel.

Try it this way. To turn transverse or semi-transverse in your canoe, place both knees into one chine. The  onside knee is generally placed just in front of the seat rail (on the onside), with the offside knee ahead of it (also on the onside). As you move into position, come completely off the seat, transferring all your weight onto your knees. This move automatically pitches the bow down, takes weight off the stern and allows the stern to skid. The canoe turns quite radically. The farther forward your knees are placed, the greater the pitch, and the more radical the skid. The farther (or higher) into the chine that you place your knees, the greater the heel. You can use your toes to help press your knees farther (or higher) into the chine. Remember: keep your nose over your navel over your knees, and avoid BOB. This technique also works when moving into a cross-transverse position, used to heel toward the offside, as for a cross axle or a cross wedge—but not the cross post (see below).

onside knee is generally placed just in front of the seat rail (on the onside), with the offside knee ahead of it (also on the onside). As you move into position, come completely off the seat, transferring all your weight onto your knees. This move automatically pitches the bow down, takes weight off the stern and allows the stern to skid. The canoe turns quite radically. The farther forward your knees are placed, the greater the pitch, and the more radical the skid. The farther (or higher) into the chine that you place your knees, the greater the heel. You can use your toes to help press your knees farther (or higher) into the chine. Remember: keep your nose over your navel over your knees, and avoid BOB. This technique also works when moving into a cross-transverse position, used to heel toward the offside, as for a cross axle or a cross wedge—but not the cross post (see below).

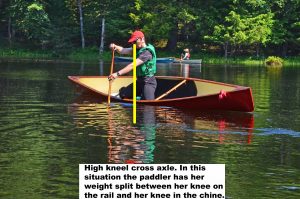

Want to heel even more? Place your offside knee onto the onside gunwale. (For an offside or cross heel, place the onside knee onto the offside gunwale). You control the degree of heel by adjusting how much pressure you place on each knee. More pressure transferred to the gunwale knee equals more heel. Believe it or not, as long as you don’t lean your head out past the gunwale, the canoe won’t tip over. Just don’t forget to keep your nose over your navel over your knees and avoid BOB.

An exception to the nose-over-navel-over-knees mantra would be a transverse (or cross-transverse) post. In this case, the goal is to heel the boat toward the offside while facing the onside. The paddler’s position within the canoe is toes in the offside chine and knees toward the onside chine. The mantra here would be nose over navel over toes. In this case, to increase the heel, the paddler rocks back transferring more weight to the toes. In a more extreme version, known as a butt post, the paddler is a bit more upright, partially sitting on the offside gunwale, which further transfers weight to the offside. A “benefit” of the butt post is that you can accurately judge when the offside gunwale is fully heeled to the water, because your bottom becomes as wet as the boat’s!

There are even more radical heeling moves, such as a high-kneel thrust or foot on the rail, and probably a few that haven’t been devised yet. Go out and have some fun. Remember “play to practice-practice to play”.