by Marc Ornstein

There comes a time for all paddlers when it’s necessary or desirable to shift into reverse. Perhaps it’s at the beginning of a journey, when you wish to back away from the dock, or after you’ve explored a dead-end channel that’s too narrow to turn around in. Has the wind or current pushed you uncomfortably close to that alligator, manatee or moose you were photographing? Whatever the reason, you now need to back up.

Most of us learned a basic reverse stroke, early on. For most, it wasn’t very pretty and didn’t include much in the way of steering. It was merely a way of stopping and perhaps moving back, a few feet. There are at least four ways to back up, all under control and with the ability to steer. I’ll cover the first here, in part one of this series.

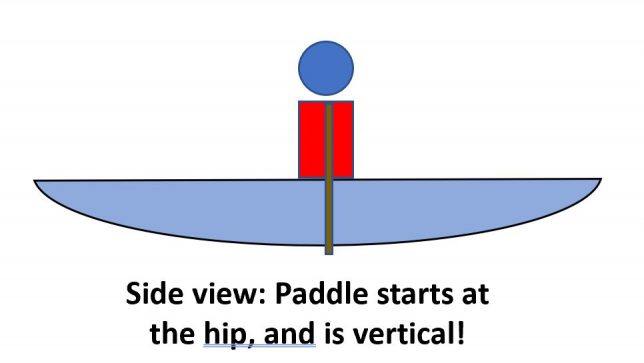

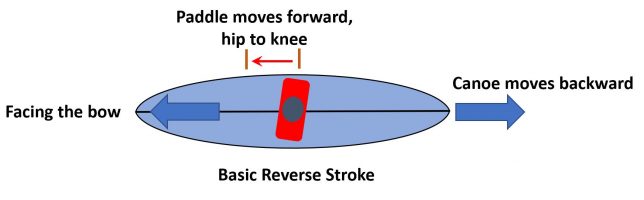

The standard reverse stroke is similar to the basic forward stroke, except that in most respects it is executed backwards. One begins by placing the blade in the water, alongside or just behind the hip. The paddle shaft is held as vertical as possible (not angled forward nor back nor side to side) with the grip hand extended outward so that it is stacked over the shaft hand, outboard, past the gunwale. The blade is nearly perpendicular to the water surface and is at right angles to the keel line of the canoe. It is then pushed directly forward approximately to the knee where it is sliced out (directly away from the canoe) and then repositioned (recovered) for the next stroke. In-water recoveries are a smoother and less awkward option but take considerable practice to master. If this is done cleanly, in all respects, the canoe should move nearly straight back, with minimal yaw. Of course, in the real world some directional control may be necessary. The channel you are backing out of may not be straight and wind or currents may be pushing the canoe, one way or another. Steering in reverse is a necessary skill.

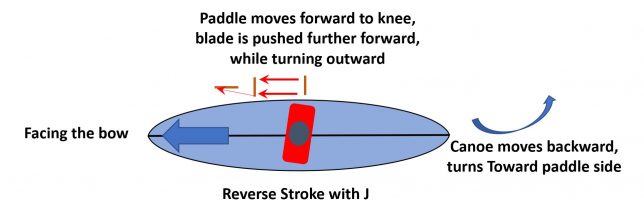

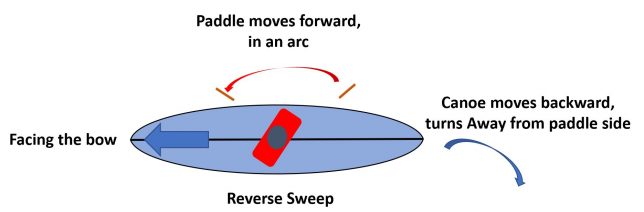

The two most common reverse steering maneuvers are the reverse J and the reverse sweep. The reverse J will turn the stern of the canoe toward the paddle side while the reverse sweep will turn the stern of the canoe away from the paddle side.

For the reverse J we’ll begin with the basic reverse stroke as described above. At the end of the stroke, with the blade approximately at your knee, you’ll rotate your grip hand (and thus the blade) so that your thumb turns back a bit towards the stern. Keep the shaft hand loose and allow the paddle to rotate freely within your hand. The rotation will generally be mild (less than 45 deg.). While rotating the grip/blade, continue pushing the paddle forward and away from the hull a bit, while allowing the shaft hand to slide up (“choking up”). The stern of the canoe will begin to turn toward the paddle side. Hold the blade in this position and allow the canoe time to turn until the necessary correction has been achieved. Pushing away too far or angling the paddle too sharply will over correct and excessively slow the canoe. Now, slice the blade out of the water and recover for another stroke. Once again, in-water recoveries are an option.

Here are videos showing the reverse J, in real time and 1/4 speed:

The reverse sweep is somewhat simpler. You likely learned a reverse sweep, early on in your paddling instruction. Back then, it was likely taught (along with the forward sweep) as a way to sharply rotate a stationary or nearly stationary canoe. In this case, we are using it in a much milder manner as a means of maintaining directional control while the canoe is traveling in reverse. Remember, the reverse sweep will turn the stern of the canoe away from the paddle side. For this purpose, the reverse sweep is much like the basic reverse stroke except that instead of pushing the paddle straight forward, with a vertical shaft as described above, we will intentionally sweep the blade outward, away from the hull, in a mild arc, while pushing it forward. This is accomplished by pulling the grip hand inward of the gunwale, or pushing the shaft hand out (away from the gunwale) or a combination of both. The further away from the hull that the blade is swept, the more turning effect it will have, but it will also produce less momentum. For purposes of directional control, while traveling in reverse, only mild sweeps are generally required. Unlike the reverse J where the “J” is a separate motion appended onto the end of the reverse stroke, the reverse sweep is simply a modification of the reverse stroke itself.

While the basic reverse stroke along with the reverse J and sweep are necessary and useful skill sets, they have their limitations. Pushing the paddle in this manner is biomechanically weak and doing so, for more than short distances, becomes tiring. Additionally, it is difficult to watch where you are going as your body is facing forward while your neck needs to be constantly twisted backward. In parts 2 and 3 of this article, we’ll explore other and often better options for traveling in reverse.