Learning the Fine Art of FreeStyle Canoeing

Sarah Reinke

Paddles flash in the angled early-morning light. Canoes arc gracefully across the sheltered pond, gunwales dipping dramatically toward the dark water as boats circle smoothly and then settle like swans. Other paddlers stop and stare in jaw-dropped admiration. Passing Church Pond en route to Lower St. Regis lake, they have unwittingly encountered a niche of paddlers practicing the unfamiliar art of freestyle canoeing.

Paddles flash in the angled early-morning light. Canoes arc gracefully across the sheltered pond, gunwales dipping dramatically toward the dark water as boats circle smoothly and then settle like swans. Other paddlers stop and stare in jaw-dropped admiration. Passing Church Pond en route to Lower St. Regis lake, they have unwittingly encountered a niche of paddlers practicing the unfamiliar art of freestyle canoeing.

FreeStyle is bewitchingly beautiful to watch. Mysterious. Misunderstood. It is also elegantly easy, once you’ve learned how to make the boat do most of the work. That is why we have gathered in this quiet corner of upper New York state for the Adirondack FreeStyle Symposium: we are putting our canoes through obedience classes.

FreeStyle can seem like an odd pastime to those who’ve never experienced it. Why spin your boat in circles without actually going anywhere? “When I first heard of this,” confesses FreeStyle student Phil Benvin, “I thought it was the dumbest thing anyone could ever want to do. Then I tried it, and now I really like it.” Those who see FreeStyle before hearing about it make more ardent devotees. A woman who was walking her dog past Church Pond while class was in session is ready to convert and join us. “I just saw all these people out doing things I didn’t know you could do in a canoe”, she exclaimed. “It’s a different world.”

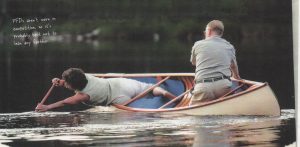

Like training a dog, training a canoe takes some effort on the owner’s part. The trick is learning the commands that give you precise control over your boat. We tell the canoe where to go with an initiating stroke and paddle placement, and then hang on and enjoy the ride. Done correctly, it feels nearly that effortless. Hard work isn’t necessarily a virtue in FreeStyle. In fact, the harder you’re working at it, the more likely that you’re doing something wrong. This isn’t supposed to be Work. It’s Play.

Just ask any of the students in the kids’ FreeStyle class. These 8 – 10 year-olds will tell you that FreeStyle is child’s play, if you can catch them that is. They zip around the pond in kids sized solo canoes, giggling as they try to lob a sponge fish into their instructor’s boat. Their next teacher, Jim Mandle, escalates the silliness by having them stand in the stern and bob their canoes across the pond without the benefit of paddles. He also has them kneel in the bow, radically pitching the boat, and spin their canoe in circles. Balance and boat control – that’s FreeStyle in a nutshell.

FreeStyle can sound hopelessly complicated to the uninitiated. So does breathing, if described in precise physiological detail. I could describe an axle as an onside turn with an onside heel, initiated with a hard J-stroke, pitching the bow down and slicing the blade forward to a static bow draw, concluding with a draw to the bow. That’s a fairly accurate but mind-numbing description. My daughter Emma will tell you that an axle is simply “the 3 J-strokes – 2 Js back and one forward.” FreeStyle is far easier to do than explain.

FreeStyle can sound hopelessly complicated to the uninitiated. So does breathing, if described in precise physiological detail. I could describe an axle as an onside turn with an onside heel, initiated with a hard J-stroke, pitching the bow down and slicing the blade forward to a static bow draw, concluding with a draw to the bow. That’s a fairly accurate but mind-numbing description. My daughter Emma will tell you that an axle is simply “the 3 J-strokes – 2 Js back and one forward.” FreeStyle is far easier to do than explain.

Out on the quiet waters of Church Pond, my class is practicing the four basic turns as cross-forward maneuvers. Instructor Charlie Wilson is not favorably impressed by the boat heel he sees. He wants to see the gunwale way down on the water and the stern way up out of it. “I want to be able to throw a cat under it and keep the cat dry,” he tells us.

I know this is for my own good. Radical boat heel is a hallmark of FreeStyle paddling. And it’s not just showing off. It helps the boat turn more efficiently by presenting a shorter, more rounded portion of the hull to the water. But I can’t quite get there yet. I may have to take remedial classes from Emma. She’s heeling the gunwale down to the water on her first day.

I’ll work on it later, when I’m expending less mental energy on getting the mechanics of the maneuvers right. That is the beauty and frustration of canoe instruction: everything you need is set before you in an all-you-can-eat buffet, but there’s only so much you can take in at one time. It takes several trips to the table to load your plate, and even longer to digest it all.

FreeStyle serves up more options than other forms of paddling. Even when discussing fundamentals, rarely do you find universal agreement. When it comes to the more artistic aspects of the sport, the range of opinion spreads even wider. Taking advantage of this diversity, FreeStyle classes get a different instructor for every session. Some students find it disconcerting to be taught something one way one day, and significantly differently the next. The general rule is to agree with the teacher for the duration of the lesson. Later on, you can decide for yourself what advice to keep and what to discard.

Charlie, our lead-off instructor, seems to expect perfection. He’s the stickler for boat heel, among other things. Day 2 instructor, Ray Halt, an exceptionally fluid paddler, is the physics professor, willing to overlook faulty boat hull to focus on perfecting stroke mechanics. In the clean up position, Kim Gass functions more like a piano tuner, pointing out what we need to tweak to make each turn ring true. What each student takes away from the lesson may be different, but we all end up with more obedient boats – even if mine still won’t heel.

What we need now is practice…lots of it. Homework sessions take place on the pond every afternoon, with instructors offering personal coaching and advice. It’s possible to learn nearly as much by just hanging around the pond for an afternoon as from class. Special Topics are offered: perfecting the forward stroke, paddling in wind and waves, swimming with your boat, and Omering. Named in honor of Algonquin guide Omer Stringer, this is the south-of-the-border name for Canadian FreeStyle. Stringer conceived the notion of moving to the middle of the boat to improve efficiency when paddling solo in a tandem tripping canoe.

Like some of the paddlers here, FreeStyle is relatively young, having originated in the 1970s. Symposium organizer Tom MacKenzie explains that it was started by a bunch of guys “just playing around in little boats”. What they did evolved into a discipline that has elevated canoe paddling to an art form. Linking strokes and turns into stylized maneuvers as fluid as the medium on which their boats float, FreeStyle paddlers resemble dancers without partners. Paddling to music was a natural next step, giving rise to Interpretive FreeStyle, seen at exhibitions and competitions.

But FreeStyle can still be a music-optional sport. We’re all drawn to it for different reasons. For some it’s the artistry that appeals. For others it’s improved boat control. For still others, it’s accessibility. You don’t need a remote wilderness area, spring run-off, or dam release to paddle FreeStyle, just a body of water not much bigger than a backyard swimming pool. For some of us, it’s just another facet of paddlesports to polish. Marc Ornstein, fellow student and whitewater paddler, said “I don’t know if FreeStyle is helping my whitewater [paddling] or the other way around.” But it’s a pleasurable way to cross-train.

On the final day of class, the kids are taken on a two hour canoe trip through a string of Adirondack ponds. When they return, our classes rejoin for a particularly vengeful game of Dead Fish Polo, pitting parent against child. Marc makes an ill-considered move and flips his boat. Daughter Sarah gleefully taunts “ding dong, the Daddy’s dead”. Marc retaliates by swiping her dropped paddle. Unperturbed, Sarah scrambles like a monkey to the stern and, with superb balance, begins bobbing her boat to shore.

As the light fades that evening, we gather at the pond for the Symposium’s closing recital. One of the performers is my classmate Jon Hammond. At age 12, he is able an agile and serene paddler. He has choreographed his own routine to music from The Lion King. He and the other performers gracefully skim the glassy water, deftly and elegantly putting their canoes through their paces. The obedience classes have paid off.

First published in Canoe Journal, 2004. Reprinted with permission of the author.