Notes Towards a Philosophy of the Personal Canoe

Mike Galt

[Ed note: Mike Galt was one of the pioneers of modern-day solo canoes and paddling. This article first appeared in Harry Roberts’ Wilderness Camping in March/April 1978. It has been unavailable for some time, but remains one of the classics. We reprint it here because it still deserves an audience, and in the interest of preserving the historical record.

Ed note 2: “Wow! I last read this piece at least ten, but likely closer to twenty years ago. I appreciate, now, what Mike wrote then far more than the last time. In many ways, he has refined my thoughts (though of course he wrote them before I conceived them). This essay should be required reading for FreeStyle paddlers.” –Marc Ornstein]

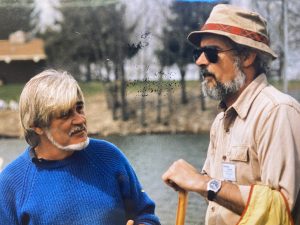

Photo Credit: Charlie Wilson, 1987 Triangle Solo Rendezvous

The rebirth of the pure solo canoe is the most exciting single event to occur in sport canoeing in this century. Paddling one of the fast, lovely canoes so common to the genre is so completely beyond the average canoeist’s experience that the introduction of the solo canoe – and the concept – must be handled in a special manner. It is said that Zen is best explained by first saying what it is NOT. What it IS may then come through clearly and cleanly. Because of the mystical aura surrounding the solo canoe, and the burgeoning cult surrounding it, this approach seems logical.

Pity, if you will, the innocent pilgrim who comes to the lakeside with romantic, adventurous visions of swift, slender, graceful canoes, perfectly conceived to carry the wilderness traveler along watery forest trails with efficiency and grace, and in total harmony with nature. The reality is often disenchanting.

Our pilgrim sees a group of weekend canoe-campers coming up the lake. They are obviously enjoying themselves. The canoes are loaded to the gunnels with cooler chests, lanterns, department store umbrella tents…all the comforts. The sound of amiable chatter and laughter tinkles across the water. A pleasant scene, repeated a thousand times every summer weekend and should be repeated a million times. We’d all be better for it. But this is not what our pilgrim had in mind.

The canoes are wide, flat-bottomed, and a bit clumsy. They move sluggishly and the canoers flail the water, switching their heavy, overlong paddles randomly from side to side. Some of the canoes are garishly colored. Some sound like they’re made of sheet metal. Some are of a plastic material that resembles a dishpan. All would look natural with little claw feet and faucets. So this is canoeing! Discouraged and disillusioned, our pilgrim turns and leaves, mere moments before the vision of The Grail appears:

Downlake the sun glints on a flashing paddle. A lone figure appears, rising out of an incredibly slender, low-profiled, open canoe. The figure dips and sways with each powerful stroke and the canoe rolls, ever so slightly, with the paddler’s body rhythm. It is impossible to separate the paddler from the canoe. They merge, a unity, a lovely, graceful, traveling being running smoothly and with deceptive speed. There is, apparently, no water turbulence around the fine, sweet hull…only a clean wake fanning out gently astern, punctuated by widely-spaced paddle swirls diminishing in the distance. As the canoe draws near, gaining rapidly on the paddling group, its bow wave can be seen to rise in a low, transparent curve against the hull. Only the pulsing profile of the wave betrays the illusion of its being painted on the canoe. Inside the canoe, the kit is neat and Spartan. The paddler has left civilization for three days to re-create, and has no wish to carry it along in the canoe.

The stern paddler in the group’s drag canoe starts as the sleek vision slips silently into view. The lone paddler slides through the pack like a destroyer through a convoy of tramp steamers, breaks out in front, and is soon gone.

A curious phenomenon takes place. I have witnessed it many times. The paddlers in the group did little more than glance at the specter that had just passed among them. There was no rapport. Their chatter stopped briefly, yet strangely, when it began again, the swift, slender canoe was not discussed. For sure, they had their inner thoughts, but their experience with the common, standard canoe simply could not generate the emotion or the language necessary to comment on what they had seen. It was too far removed. They could not relate. They were the pick-up truck folks who didn’t know quite what to say or think when the sports car blew past.

To the average canoer, the familiar tandem canoe is little more than a hum-drum, uninspired, floating platform…and he or she is content with it as it is. Relatively few tandem paddlers ever become singlehanders. Most soloers come from the ranks of other self-propelled recreational pursuits where high-performance equipment is the norm rather than the exception.

The solo canoe has taken its place next to the contoured packframe, the torsion box touring ski, and the ten-speed touring bicycle – sophisticated equipment for today’s outdoor people. In a sport that has shown precious little class since the days of J. Henry Rushton, the arrival of the solo canoe was long overdue.

THE CONCEPT

The solo thing isn’t new, you know. As a matter of fact, it is just now coming full circle. When sport canoeing was in its heyday back in the 1880s, everyone paddled solo. It was an utterly natural condition. And the canoes were low-ended, sweet, fast, and wholesome. Gorgeous they were, built like violins, and finished naturally with rubbed shellac and hard carnauba wax.

In the 1890s, America’s love affair with things mechanical began in earnest with the bicycle, and the popularity of the solo touring canoe waned. In order to rekindle interest in the sport, the less expensive, canvas-covered tandem canoe was introduced. The type became an overnight sensation…not with wilderness travelers, but with courting couples in search of a little privacy in the middle of the town lake. In response to its new use, the tandem canoe became wider and more flat-bottomed – a platform, if you will – to encourage all sorts of carryings-on. There is no doubt that our grandmothers have had a great deal of canoeing experience. More than likely, she’ll tell you how fast and lively Grandpa was!

This was all great fun and infinitely more appropriate and joyful than the back seat of a Ford sedan – but in the meantime canoe design suffered horribly. The clumsy, non-performing courtin’ canoe continued to be built long after World War II. These were truly the canoeists darkest days. In the Sixties, the light began to shine again as fellows like Ralph Sawyer, Charley Moore, and later Jim Henry, began producing fast, lightweight, wholesome canoes once more. Walking became popular. The bicycle became popular again, and now, in 1978, the svelte, exciting, solo touring canoe has returned. The circle has closed.

The open solo canoe fills a gaping void in the varied array of self-propelled sporting craft. These fast, handy canoes are to flatwater what the slalom kayak is to whitewater. There is a bond, a kinship, between the paddlers and a high level of paddling skill that the devotees of both types seem to naturally strive for.

Sport paddling, that delightful recreation that takes up the slack between wilderness cruises, is where the solo canoe really shines. In my area, we meet casually at a pretty, three acre pond simply to play on the cool clean water. In one corner, a four buoy slalom course is set up with milk jugs. The competitive types hang out there and time each other through the sequences. Another group is toying with an impromptu precision paddling routine. Others flit about the pond polishing techniques, showing off, or just grooving in the warm sunshine. There are taunts and peals of good-natured laughter from the spectators when someone dumps attempting an outrageous, playful maneuver. Play! Write that word down. That’s what it’s all about.

Almost half the paddlers are women, and they handle the small, light canoes with a delicious skill and finesse. On the slalom course, their best times equal the average man’s – and slalom is muscle as well as skill. When the women work with the precision paddlers, the men look like clumsy oafs. It works out.

While cruising, the woman’s spirit sense of the real world and endurance make up for her less imposing musculature. Recently, my wife and I were working across an open bay against a stiff headwind and a short chop. I was bone-tired, and as my strokes became erratic, I began to lose that lean hard edge of positive control of my boat. Milly drew alongside, looked at me, smiled, and said “Mikey, did you see the osprey?” She knew! God, she knew! I pulled it back together and we soon made it into the lee, strongly.

Women are fleeing the dreaded bow seat at an alarming rate, and as individuals, are settling themselves into solo canoes. Welcome aboard!

The solo canoe will become your companion, ready in an instant to take you anywhere, yet content to go nowhere…nowhere further than a nearby lake, or quiet stream on a soft morning, or a balmy moon-lit evening. Gliding softly in a small, quiet canoe along the shoreline of a familiar waterway opens up a world you never knew existed. You’ll enter this world gently, with respect, and the wild things that live there welcome you as a friend and go on about their chores as you slip past. Often, on these brief jaunts, you’ll find yourself mesmerized by the motion of the canoe and the mood-rhythm of your own stroking. Caress the water with your paddle and, as the canoe traces lazy patterns on the calm water, go with it. Dance with your canoe a dance as graceful as any mating ritual in the wild. When the music ends, you’ll be wearing a faint, secret smile. And you’ll understand the mystique of the solo canoe.

Gibran suggests that “Togetherness is not drinking from the same cup, but rather from each other’s”. And so it is, as the two small canoes move slowly in the stream side by side, inches apart, separate yet in perfect concert, the people speaking softly, touching. Then, as the spirit moves, breaking apart – she, in a graceful banking turn to pick a wildflower from an overhanging branch; he with a whoop and a slashing exuberant pirouette. They glide back together and a flower is traded for a kiss. Togetherness!…in solo canoes.

The solo canoe is not for everyone. It is for special people. Given a chance, it can also help people to become special.

THE CANOE

If the solo canoe has one outstanding characteristic, it is slenderness. This feature is inherent in the breed and is ultimately responsible for the type’s sparkling performance. Why must it be slender? To effect proper trim attitude, the solo paddler must be situated in the center of the canoe. The canoe must be narrow enough at this point for the canoeist to reach the water comfortably with the paddle and stroke efficiently. Thirty inches (at the rail) is the maximum width for a true solo canoe.

Length? All things being equal (shape and proportion), the longer the canoe, the faster it is. In other words, speed is a factor of length. I might mention that once you’ve tasted the effortless, driving speed of a fast canoe, you’ll never be quite the same. Speed is necessary for beating out a thunderstorm or reaching a distant campsite before dark. Speed translates to “ease of paddling”. Speed is well…speed is just plain nifty!

A canoe that is too long can become unmanageable in conditions of heavy wind and sea. It may also be awkward to handle out of the water. The proper length for efficient, high performance touring is about sixteen feet, plus or minus six inches. The marathon competitor may (or may not) opt for a bit more length, while the sport paddler, women, and weekend cruisers may prefer a shorter canoe.

The “shorter” canoe creates an interesting category. While the beam must still not exceed thirty inches, the length may range from the 10 ½ foot “Rushton” type, to the lower range of the serious touring boat, about 15 ½ feet. I would tend to classify a solo canoe up to 14 feet as a “personal” canoe. A canoe anywhere within the entire range may be a “sport” canoe, depending on its intended use. A sport canoe would probably not have the intense tracking qualities of a pure touring boat.

The “personal” canoe may well prove to be the most popular of all. They are a joy to paddle and are convenient and lightweight. They can be poked in the back of a van or station wagon, and they are light enough for a woman to place on a cartop without undue strain. I know a lady who keeps her 13 ½ footer in her groundfloor apartment. It hangs on the wall above the sofa.

There is a fashionable trend towards ultra-light canoes. Some exotic 16 foot solo racing canoes weigh in at under 20 pounds. Canoes of this weight are truly marvels of engineering and are excellent for sprint conditions where the paddler must get off the line instantly. The racer’s short, rapid, choppy stroke calls for light displacement and minimum wetted surface. The day-tripper or cruiser may do better with a bit more weight. A canoe that nestles in the water and has the weight to “carry” between strokes would respond better to a cruiser’s longer, slower stroke. There is, of course, the argument that ballast can always be added to a light canoe. This is valid. You can place the ballast exactly where you want it. Personally, I don’t want to be bothered with sandbags, and I don’t find a 16 foot, 40 pound canoe unhandy. But I’m a big shaggy bear. Give some thought to the weight thing.

Many persons wonder about the stability of the slender solo canoe. This question opens up a can of worms and I’ll answer it like this: does your ten-speed have training wheels? When you bought that pair of superskis, did they come with a guarantee that you would never eat snow? Of course not! Sophisticated equipment not only deserves competent, skillful handling, but demands it! The rewards for developing the essential skills are enormous. The paddler will have earned the honor, and the joy, of having mastered the most exciting self-propelled water craft extant.

Now I’ll back up a bit and turn it around. Yes, the narrowest of solo canoes should have stability. Not the dreary, raft-like stability of the flat-bottomed standard canoe, but the lively, dynamic stability of a living thing. Firm final stability however, is absolutely essential in a touring boat. This is the feature that permits the canoe to roll through its arc, begin firming up, and the STOP before the rail goes under. Final stability is the result of hull design and has nothing to do with the width, Many racing canoes utilize excessive tumblehome for paddling convenience, sacrificing reserve and final stability. I have found this type of canoe to be rather vicious and unwholesome and entirely unsuited to touring. A good test is to kneel in the canoe, grasp the gunnels, and roll it from rail to rail. If you dump, you might keep shopping.

On this matter of shopping for a solo canoe be forewarned: the staff in the vast majority of shops and stores that sell canoes has an abysmal knowledge of (even!) standard canoes. To expect those dolts to know ANYTHING about the new solo boats is beyond all logic. Stick with editorials and articles in Wilderness Camping for your information. Again though – be forewarned. The editor loves fast boats almost to a fault, and will tolerate – and even prefer – some nasty little nickel rocket with no reserve stability because it’s more “efficient”. But he can make the ugly little brutes dance!

THE PADDLE

You can’t paddle a classy, sophisticated canoe with a dime-store paddle. But before we get too deeply into the paddle, paddling style must be discussed. Harry Roberts to the contrary and notwithstanding, I do not like to see solo canoes paddled from a sitting position. Racers use this style with a bent paddle and change sides every few strokes. It is super fast, awesomely efficient, ugly, boring, and turns a canoe into a piece of floating gymnasium equipment. If you paddle for pleasure and want to feel and understand your canoe, you’ll kneel. On both knees, on one knee, high on one knee, you’ll kneel. Now if you’re getting a bit creaky like me, and no one’s looking, you might push back in the seat once in a while to get things sorted out, but basically you’ll kneel [Mike, now you know why I sit? HNR]. And in your solo canoe, you’ll use a straight shaft paddle.

The solo canoeist’s paddle is a magic wand rather than a flattened club. Most of us keep our paddle in the house because it feels nice to pick up and heft once in a while. It should be wood! The entire

paddle, from tip to grip, must have a tough, resilient flex. This softens the shock-loading on your arms and shoulders and permits hours of mile-devouring, rhythmic stroking. The shaft should be oval in the area of the lower grip for strength and comfort, and the blade should have a smooth “airfoil” section to reduce the turbulence. More than anything, it should “feel right”.

The best boughten flatwater paddles are made by Clement. Whitewater paddles tend to be too heavy and stiff.

The best blade patterns for straightaway cruising are the “Sugar Island” and the “Square Tip”. Both styles have the squarish ends so well suited to the soloers classic hook stroke. For showing off and slalom work, I invariably use my lovely old spruce beavertail, with its long 29 inch blade. I’d place the maximum length for a cruising blade at about 26 inches. Width? About 8 or 9 inches, depending on how easily your canoe moves and a realistic appraisal of your own strength. A small person might use a 7 inch paddle.

There’s usually money for a paddle long before there’s money for a canoe, so we’d better get you sized now. To determine your proper shaft length, kneel astraddle a gallon paint can, and plop your rump on it. Now measure from your chin to the floor (water). Add this to the manufacturer’s stated blade length, in the pattern you like, and you have your overall length. This is about as close as you can come without actually kneeling in a floating canoe and measuring.

While the pure, open solo touring canoe may be an exotic newcomer to the modern canoeist, its recent heritage may be traced back through the mists to the origins and development of Howie LaBrant’s C-1 Delta Olympic canoe, a fierce, bizarre, thrilling canoe that may only be described as resembling a supersonic butterfly. And solo paddling technique and style – so classic, so pure – has been perfected and preserved through the generations by a small, dedicated, elite cadre who may truly be regarded as canoeing’s royalty. But it’s a royalty anybody can attain. All you need to do is to know something.

May the wind be at your back…